Barajul - The Dam, poveste semiliterară, dar adevărată

I lived well among childhood's charming things and temptations until about the age of 13 Then some people began to build a dam in our village. From it came all the trouble in my life, I used to think with bitterness. Life has not been the same since then, and death moved from the city to mow down at will the elder and younger people of the village. Before the dam was there, the river was impetuous and foamy like a horse ambling fast, getting lost from its traces. Almost every year floods covered the ground and even a small tributary creek puffed and burst out of its otherwise gentle nature. When I had to go to the station, my grandfather carried me piggyback, almost always joking that I held his neck too tight for fear of slipping as he carried me over the water. Village elders said that 50 years ago the river froze more than a meter wide, and in summer they washed hemp crops in the river and caught big, sweet fish there. Those were story-like times when waters were clear, before chemical plants blackened river. Many years before the dam was completed, villagers and others passed over a narrow bridge that swung between two poles, sometimes making one shiver with fear. In time planks rotted, a few went missing, and the icy ones in winter were a real danger to step on. From time to time rumors came that someone had drowned there. The river also took its toll in lives of horses lost on an islet when their master could not find them. Wagons and cars traversed the river on a cable ferry gliding on a thick rope of steel. A Gypsy man was hired to spin the crank, guiding the “ship” from one bank to another. He slept in a mud hut on the village shore. The last one, Nicholas, was lost to the world from that village after the dam was raised. Another additional victim.

There were two engineers in my family. One worked in hydroelectric power, and he visited the village when I was still small. The second was my father. My father was a road engineer. One evening, sitting with us around the table, he revealed he had learned of a secret government plan, that a dam was to be built on the river and that the village there was to be demolished.

My grandparents did not believe him, but all of us were a little scared. The years passed and I found that somehow my father was right: nothing there was like before; the hidden paradise of my childhood was gone, and gone were the local inhabitants and their orchards stretching towards the riverbed.

In the summer of 1984 there was the traditional “village sons meeting,” where young and old, villagers and guests and children of the village gathered together, people willing to talk and listen to music, and to dance. One sunny day we walked to the meadow next to the river. I was among the youngsters.

Dam works were already underway. I remember piles of gravel and rare green grass. But we, the children, had no worries. It was the first time I tasted beer, only a little, because they did not sell juices. The next meeting of this type came 27 years later, when people, much fewer in number, came to the village on the road built over the dam.

There was neither the boat nor the footbridge, which boys used to swing, to annoy girls, and from which some of them jumped into the river to swim. Our house was located at the end of the village. It was among the last ones to be reached by the old way. Today it is one of the first you see after descending the road from the dam.

Many years cars did not use to go there. The road was filled with dried-out old wagon ruts, with cattle dung; children often walked barefoot there or made mud pies while playing in road dust and water. After the dam was built, the wheeled wooden chariots were replaced by cars bringing relatives to the village, passing in front of our windows.

We had a neighbor who was deaf. I saw her often when I was little. She took water from the street well because she did not have one of her own in her yard. She wore the traditional folkloric blouse. She had a large, open smile that stretched to each corner of her head kerchief, and she talked loudly. Sometimes I felt repulsion; I did not like her to kiss me on the cheeks. But she was warm and generous, coming unexpectedly to our gate with her apron full of luscious, sweet golden pears... so wonderful.

Our other neighbors were few. Among them was the German cobbler, in whose house I tasted maybe too many sweets prepared by his wife. When I grew up, some village children, with whom I played in the evenings, proposed once an “adventure”: to go “stealing” pears from another neighbor. As a kind of joke, not to do evil or damage. I did not agree, but I could not spoil the mood of the others or renounce their company. I watched them skip over the stone fence and then come running back scared of some dog, disappointed that the pears were too raw.

Then I heard shocking news. One of that neighbor’s sons, a foundry worker, had died boiled alive in the factory’s boiler. I remembered that death my whole life, it was an accident which can impress the mind of a child. I thought the poor man must have suffered a lot.

The dam was completed after many years, in the nineties. The large majority of my mother’s generation had left to live in the city. Only a few new folks came from other places to settle in the village. One after another, old houses with cross-marks on the wall and with shuttered windows concealed empty nests.

For unknown reasons, Gypsies robbed and killed the village priest. Another gang of thieves ransacked deserted houses and looted the church. Then it was renovated and restored. One day I heard something else that threw a shadow over me: the river was demanding its rights. An old woman, the neighbor who brought me luscious pears when I was a child, drowned in mud near the dam. God knows what she gathered there, maybe brushwood for fire or maybe she was lost in thought about the old world, where that place was filled with dry gravel and was a wonderful backwater. I remembered the other neighbor drowned in the boiler of the factory where he worked. Both were people from the village of yesteryear, like us. And both drowned in something else, not in water.

Flooding did not stop after the dam was built. More trouble hit the Gypsies of the village, with their small huts and houses around another tributary of the river. Water also destroyed completely the house of the former cobbler, where someone else now dwelt.

What have I left for myself? From what was there before, nothing. My grandparents rest in the small cemetery. The area around the dam became a reserve for the protection of wildlife and plants. The riverbed is enclosed with barbed wire. Fishermen from different places began coming to the shores of the lake, and they still do. Unknown people bought land and raised new homes outside the village, near the lake.

Our house is one of the few houses built among three wells. Now the cellars are dry; waters do not get in anymore. I am inclined to believe that one day everything will dry up, apart from the now-tamed river. The world will be quiet again, free of car engines and other sources of noise and dust. The air will be cleaner, and the blue mountains in the distance will grow bluer.

Copilăria mea la țară (My Childhood in the Countryside) - scriere gen mărturie

Back when my parents did not have their car we went each summer to my grandparents’ village located exactly in the middle of Romania, first with a fast train. Then we took another slow train to reach our destination. Lord, how much I loved traveling by train! I admired the scenery all the way, but I preferred talking with people on the train. They were so kind and welcoming, asking me many things and giving me sweets or trifles. And when I grew up a little I was always happy to talk with other people telling me their life stories and I began to dream that I could help others in the future. The return to Bucharest was easier and cheaper, I came back with a slow train. I remember one winter when my grandmother brought me back to the city, and we were snowbound spending almost the whole night in train (such a delay never happened again in my life). I never liked to learn by heart the names of the stations because I wanted that journey to remain like a dream. Our small village station was closed after 1989. There was also a window for tickets and toilet and a well like in many stations, where I used to taste water before taking the slow train on our road back to Bucharest.

Stepping down from the train, we walked on the long and dusty road lined with poplars. Over the green river’s meadow, over a small creek where I played as a child, (even now I almost feel slippery stones under my feet), where water was clear, women washed clothes or wool there, little fish swam in it. We passed over the big river on a small suspended bridge and if it was broken (damaged by storms or snow) on the cable ferry gliding slowly, that was named “ship” by the villagers. Usually a Gypsy man held the job of transporting wagons or cars on the cable ferry, he had a hut on the other shore and we were calling after him. That suspension bridge was an opportunity for dangerous childhood games (boys annoying girls, rocking the flimsy bridge to scare them or jumping directly in the water from up there) and it was swinging even at small weights, certainly fascinating for a child. Then we had to walk for a while until we reached the other end of the village where my grandparents' house was the only house in the village with a crucifix in front of it with Christ hand painted.

The village was built between hills, in fact between the river and a long hill named “The Rib” guarding all village houses. Sometimes waters flooded the lower houses and the meadow. My grandfather took me across the water on his back and I was very happy, I was a child fascinated by the natural world, so rich in beauty and wonders. But I must admit that I started to discover the beauty of wild places only when I was twelve years old or so, because until then I was too small to understand and I missed my other grandmother living in Bucharest. In the beginning it was boring to spend the entire summer holidays in the village. Usually my parents left me there the entire summer.

Village houses were built along the main street, side by side. There were two drinking water sources, but the one near our house had gone dry before I got there as a child, so I went frequently after drinking water with a one or a three liter pitcher in my hand. In the center of the village there was a crucifix (cross) covered with a roof, where people gathered in earlier times for ring dances, games and story telling. There was also a huge scale for hay carts. Almost all village houses had crosses engraved in their walls under the eaves and benches at every porch where people sat down on Sundays to talk and watch others go by and old women waiting for the herd to return in the evening from the pasture. They told me that even pigs were taken out in the old days to graze in the grass near the village boundaries. The village had once a flourishing period, there were many other houses and two churches above the main street (where only ruins remained), because the young ones (my mother’s generation) left to find their fortune elsewhere. When I was little I had been with my grandfather to the farrier workshop and I was allowed to heat up the bellows, watching our horse being shoed.

There was also a primary school and the village local store (with a mailbox nearby) where a seller came on bike and where I stood staring, buying sometimes a few things I liked: sweets, notebooks, stockings. Gradually I was received in many houses in the village, where I found ornaments resembling those in our home (towels, woven carpets, icons) and people were also very kind, but I was too shy and it was hard for me to yell from the street their names when I was sent by my grandparents to someone else with different tasks (in those times door bells were rare). One of my grandma's cousins gave me beautiful flowers, other women did the same. The peasants had beautiful old names with Latin origin. There was also a shoemaker of German origin, living near our house, where I asked once for too many cookies or candies prepared by his wife. I think I was a greedy child for sweets like that.

Our house was isolated from other houses, we had a garden and a large courtyard paved with stones. The household was thriving, with daily hard work, with many cattle and sheep. I loved to stay in the stable at milking hour, we had buffaloes and sometimes I sang little improvised songs, perched on the opposite manger, where some brooding hen ruffled furiously her feathers. I wondered why the buffaloes had no names. It was sad for me to see the calf slaughtered for feeding us and I prayed in vain for his life, but the meat was one of the best I ever tasted. I suffered a lot when I saw it being whipped to enter its enclosure before my grandma milked its mom for us. Sometimes I approached the calf, giving it sugar, feeling its rough tongue scratching my palm, caressing it between its small horns. I was also approaching our horse with some fruit or grass, but very carefully. I never was allowed to milk, because buffaloes are by nature dangerous animals. The horse too was big and unmanageable, my grandparents did not let me ride it (other village girls went riding on the street and I envied them a little). Once grandma was in the hospital after a hoof kick and she suffered a long time. When the herd came back in the evening I waited at the gate, armed with a stick (useless of course). I had to hide in the yard, especially when I wore red cloth.

In our house I found many old things and mysteries. Everything was left there as before - iron stoves giving heat for a short time (in the morning it was very cold), many ceramic plates hung on slats or walls, ceiling beams and thick planks on the ground, covered with mats. In the bedroom of my grandparents they placed a protective nylon where once I choked a mouse. But I stayed a long time on the floor with my hands pressing the poor creature, because I was afraid to take it out - finally my great grandmother came and threw it to the cat. In the table drawer there was an old wooden pencil case with pencils and pens, from which I took out drawing tools for my princesses and fairies. Simple icons were hung on the walls, they were copies printed on paper. I was fascinated by small niche-cupboards built in the walls. My granny kept inside her glasses, prayer books and candles for storm, because she prayed when it was thunder and lightning. Grandpa kept in old photos and documents. I was impressed by an old pepper grinder with a crank. Years ago my grandparents did not have a TV or a fridge a long time; the whole household was in a prosperous state, but obsolete, maintaining traditions, without any sign of modernization, as if time stood still there, but in a pleasant way. In the bedroom we had a cuckoo clock and a mechanical sewing machine. There were so many things to discover in every corner ... and they did not change for a long time.

Grandpa was an expert when it was time for slicing pork in winter, teaching me the anatomical parts of the slaughtered animal. Grandma was so kind to me. Apart from cooking delicious food, home-made bread, gorgeous cakes, incredibly delicious pies, she used to sing beautiful Christmas carols and she also taught me some prayers. In the winter holidays season it was so nice to hear the street carolers singing. Once I even had a Christmas tree, although such trees were rare there, grandpa found it somewhere. In the evenings my grandparents played with me, we tickled one another, making jokes. Grandpa brought once a horse foot tightening rope and he tied my legs saying that I was too unruly. We all laughed and everything was so magical. My grandparents were still young; they were wed when she was 17 and he 21. Grandma wove every winter on her old wooden loom. Those times women gathered in each other’s house to spin wool. I learned by heart the cycle of wool gathering and processing, from shearing sheep to carpet weaving. Grandma also knit in the evening, but not too much, especially wool jackets and thick socks or mittens. Grandpa brought from the city bottled juice and sweets or white bread. I sat next to the table and it was fun to watch him put in the bottle for soda those small gas bombs, then combining soda with sour wine from the cellar, sweetened with a pinch of sugar. I loved to watch him sharpening his scythe and many times I went with my grandma in the fields bringing lunch to the workers around 10 a.m., because they had been mowing since dawn hours there.

They worked daily the whole week and Sunday was really beautiful, holy and Christian. The priest came in every home with baptism in January, when he consecrated drinking water in people’s jugs. A funny story with a turkey happened to me once. I was bringing home fresh water in a pitcher and a turkey attacked me, fidgeting around me. I decided to stand still. I was like a statue in the middle of street until the priest who lived nearby or someone else came and chased the frightening monster. That happened because children said that when a bear attacks, you should better fake death.

I liked so much to play with other children there, hide-and seek or different other games, staying late at night on the street, sunbathing near the river or taking a walk to the forest. Other times I liked the hay working days, but I was spared of all that harsh work. I had to force the rules, and then my grandparents seemed to be amazed about my skills. I came back home on top of fragrant hay, holding that woden pole that was above hay in order to maintain my equilibrium. It was so beautiful in the forest when we gathered dry wood for winter, where trees of different varieties grew together. My grandfather knew all their names.

At home I used to collect eggs from our hen nests, climbing on ladders, and I fed hens and chickens in the yard calling them before dusk. I watched the hierarchical relationships between winged creatures and their habits. Tiny yellow or black hatchlings were so delicate. When it was cold in autumn (and the last series of chickens hatched), they gathered close to the stove in our courtyard kitchen and I kept them in my palms. Once again I broke the rules around me (because I was supposed only to read or to play around), and I cooked the first meal of my life there when I was twelve years old: rice and tomatoes with marrows. We had a small garden inside the big garden where flowers grew every summer (hawthorn, dahlias and basil) and we had also beans, carrots or other vegetables and spices. What a marvelous scent! Nearby there was a well were I had my fish, once caught by my father, a fish who lived in cold waters a few years. When it was sunny, grandma rinsed laundry there, bluing it with small chemical cubes.

Only when I grew up I began to discover there the charm of nights filled with stars, which were fantastically bright and so many there that I felt like floating on unseen wings, as if they were pulling me gently up from the earth. I grew there in my childhood in slow motion cradle of emotion.

CONȚINUT ADULT NUMAI CÂTEVA CUVINTE VULGARE, ESTE UN BLOG PENTRU PESTE 18 ANI, FOARTE TRIST, NERECOMANDABIL PENTRU CEI INCULȚI SAU PREA TINERI

Vă vine să credeți că din țărână cresc trandafiri, copaci înalți, case și oameni? Atâta frumusețe incredibilă. Hai, recunoașteți... chiar puteți crede că toate cresc din pământ așa frumoase?

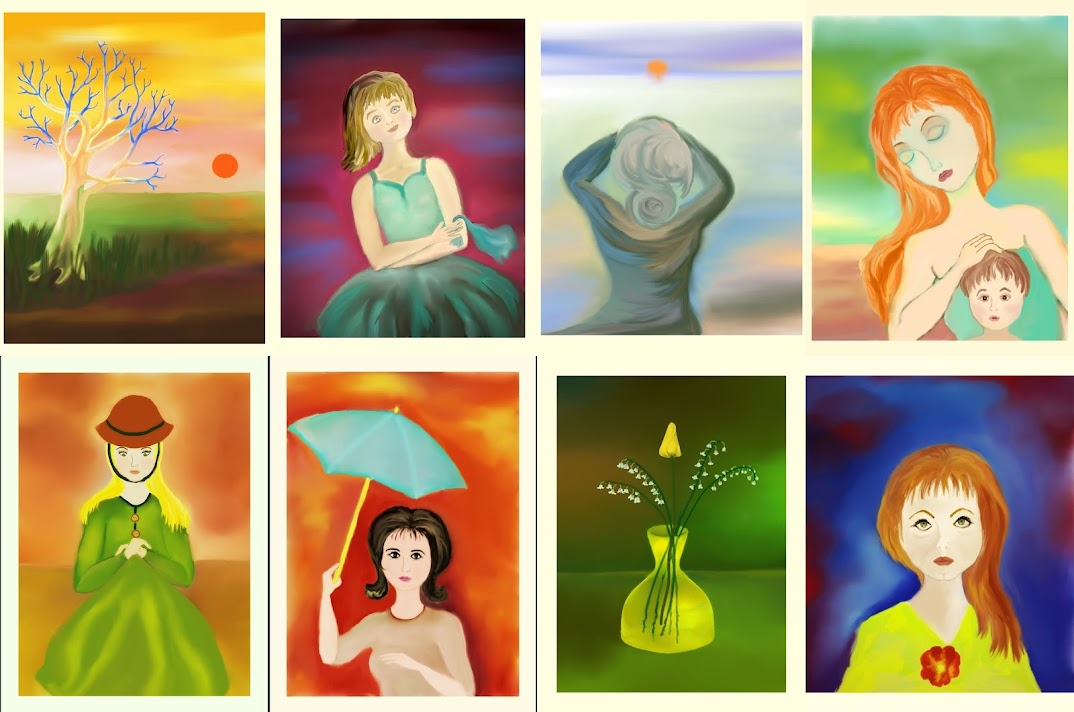

desenele mele cu mouse-ul - o parte din mine, le postez aici fiind complet izolată de peste 38 de ani, probabil le voi șterge

Abonați-vă la:

Postare comentarii (Atom)

Postare prezentată

Ultima parte – CONCLUZII - enumerare

Concluzii, partea 1 Azi, 12.12.2020, încep să scriu ultima parte a acestui blog despre viața mea. Iar au intrat în mintea mea cineva în li...

Niciun comentariu:

Trimiteți un comentariu

Cu sinceritate cred că...